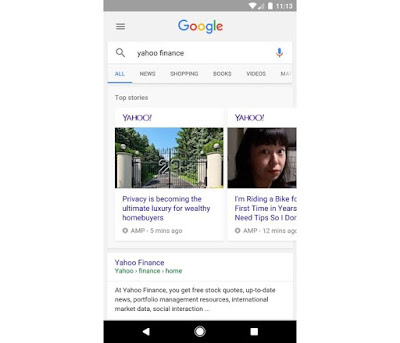

How Google is Remaking The Mobile Web

If

you’re reading this story on your phone, you may be confused about just

where on the web you’ve gone. The banner at the top of the page reads

“Yahoo Finance”—but the address above it probably starts with

“google.com.”

Google

has not, in fact, taken over Yahoo. But it is trying to fix a basic

problem with the mobile web: sluggish performance — at the cost of some

confusion and concern among readers as well as writers.

Article, meet AMP

Last

year, Google set out to craft a faster, lighter way to publish stories

on the mobile web. The answer, developed with the help of news

publishers and advertisers, was a stripped-down, open-source format

called AMP, short for Accelerated Mobile Pages.

AMP

sweeps many of the traditional components of a web page off the table,

dumping things like media embeds, interactive scripts and ad-tracking

code for the sake of speed. AMP pages load content selectively, skipping

bits that aren’t visible or about to become visible on the phone’s

screen.

“We

find that an AMP page loads four times faster and uses 10 times less

data compared to a non-AMP page,” said Google news head Richard Gingras

at a presentation during Google I/O conference in May.

That means readers are less likely to give up on a page that takes forever to load and more likely to stick around. In a Google-sponsored panel at the Online News Association conference

in September, Washington Post senior product manager Dave Merrell said

AMP stories loaded 88% faster than traditional mobile-web stories.

Readers of these accelerated pages were also 23% more likely to return

to my former employer’s site within seven days.

With more people getting their news on mobile devices — 72% in 2016, versus. 54% in

2013, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey — that

difference matters. That’s why so many publishers, Yahoo Finance

included, have started publishing in AMP. Google says more than 700,000

domains now post in AMP.

Caching and searching

I

can’t think of anybody who would argue against quicker, slimmer news

pages — except, perhaps, executives at wireless carriers who may now

have a harder time selling bigger data buckets to subscribers.

(Publishers who find that some material can’t be published in AMP because too many elements aren’t compatible while others require tedious coding—not

that you as a reader should worry about that. Let’s just say that

labor-intensive publishing software is not exactly a novel development

in newsrooms.)

But

AMP isn’t only a page format. Google also offers AMP publishers an

additional speedup through a free caching service, which is where those

“google.com” addresses come in.

Free

and fast delivery of a story may be difficult for publishers to turn

down. But that also scrambles sharing: Even though the address for

Google’s cached version of the story will take you to the original

address automatically on a non-mobile device, it’s bound to confuse

people who see “google.com” in a tweet or a Facebook post. As

Apple-centric blogger John Gruber griped on Friday: “AMP traps mobile users onto google.com.”

This

Google caching also puzzles me when I see a google.com address in my

browsing history and think it’s my search for a page instead of the

actual thing.

AMP

adoption — or avoidance — can also affect how a publisher appears in

search results. Google says AMP doesn’t factor into search rankings, but

it’s also said that it may soon start to assess a mobile site’s speed. It already highlights AMP stories with a lightning-bolt icon.

Further, the illustrated carousel of current stories you’ll see on the first page of a mobile search only features AMP pages.

If Google follows through on a recently-revealed plan to create a separate mobile search index and the company updates that more frequently than its desktop default, AMP may become even more influential.

Proprietary alternatives

I

hear a fair amount of anxiety in the news business about Google’s move

to lift up mobile publishing in a way that leaves Google with even more

leverage over the industry.

But the other easy ways to speed up mobile news inflict even worse drawbacks.

Facebook’s “Instant Articles” format is owned by Facebook (FB).

And unlike the open-source AMP, you can’t start publishing stories in

this format on your own site and then tweak the underlying code.

Apple News, the feature Apple (AAPL) added in iOS 9, represents even more of an island, since that app only runs on iOS devices.

And

while publishers can also flee the web and get more control over the

presentation of their content by shipping their own apps, that puts them

under the app-store rules of Apple and, to a lesser extent, Google.

An

open-source mobile format that anybody can use and improve without

permission doesn’t seem so bad in comparison. It may be that, as

Google’s Gingras said in his I/O talk on AMP, “this is the way it had to

be.”

But this still represents a major rewrite of the mobile web. Not for the first time, it’s Google’s world, and we just consume content in it.

Comments

Post a Comment